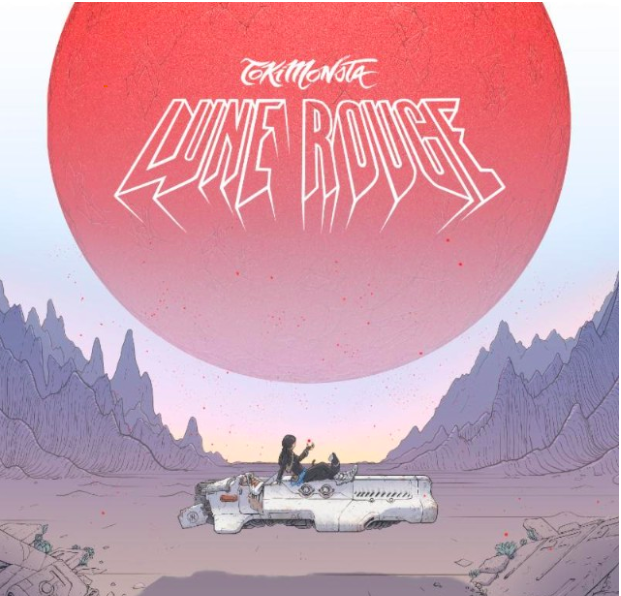

If you follow astrology or believe in the power of the moon, you know this year birthed many divine lunar marvels, including the Great American Eclipse on August 21st. The last time the moon totally eclipsed the sun from coast to coast was almost 100 years ago, and like any new moon, a solar eclipse represents the end of one cycle and the beginning of something new. Lunation that appears red has a message all its own; red is often affiliated with stubbornness, confidence, courage, passion, aggression, honesty and standing out in the spotlight. A red moon is said to represent self-awareness and our ability to survive and thrive, both of which encapsulate the story behind TOKiMONSTA’s latest release, Lune Rouge, meaning “red moon” in French. “A red moon is a rare and pretty awesome event from a scientific perspective,” she told us, “and to me means significant change.”

Producer and DJ TOKiMONSTA was born Jennifer Lee to Korean immigrants. She sat across from us at Ace Gallery in Los Angeles, fitting right in with the collection of contemporary art. Lee is a woman who always speaks with intention. Comfortable, but not outspoken; easygoing but direct. Lee’s last nine releases have propelled her from creating beats in her dorm room on Fruity Loops software to traveling the world, producing unique albums with their own individual soundscape and story. Each album keeps you captivated from start to finish, a feat few artists can accomplish in an industry that seems focused on the next big single.

Lune Rouge is her third full-length album, recorded after two brain surgeries for a rare neurovascular condition called Moyamoya. The procedures left her unable to comprehend language: “I could still think thoughts,” Lee explains, “but all the words I knew were gone. I even tried texting people, and my texts were complete gibberish. It was almost like suddenly I spoke a different language than everyone else.” She had to relearn to walk, and most devastating of all, she was unable to comprehend her greatest passion: Music. “All music just sounded like noise,” she recounted to Pitchfork recently. “I remember being like, ‘Ooh, this is weird! This is metallic, harsh nonsense to me.’”

Her recovery was grueling, but there were more struggles to come. Body reeling from surgery, she suffered perhaps the most universal ache: “My boyfriend broke up with me—after my surgery, after taking care of me,” Lee reveals. “I got dumped by someone I loved a lot while I was still recovering from surgery, still slightly unable to walk, still working on my language, still unable to make music.” But being the woman she is, she took the blow with elegance and grace and created art from the heartbreak. “That moment was probably the worst I’ve ever felt in my entire life. But that sadness allowed me to regain some clarity. I knew I had to overcome it.”

And she did, painting a picture of grief and triumph with fellow artists like Malaysian singer-songwriter Yuna. “We could talk for ages when we got in the studio together,” she told us. And as she noted in the press for her new album: “I’m super grateful to have created a song with Yuna . . . I was a fan of hers for a while, so I have to shout out the world wide web for allowing two people on different continents the ability to create together. The message of the track is really more than unwanted phone calls, but the idea of people deciding to show up only when they need you.”

The last verse of their collaborative song, “Don’t Call Me,” illustrates their message of anger and weariness at a two-faced ex:

“Funny how when you see you’re glowing up,

Wanna try and make it up

Suddenly just showing up

Where were you when I was crying?

Left me on the floor just dying

Can’t come to the phone, realign

Now you wanna be my friend, but I ain’t buying it”

Lee has never been one to shy away from a challenge, however. Don’t let her gentle demeanor fool you. She has shattered barriers for women and women of color in the electronic music industry, often unknowingly, explaining time and time again that “[she’d] rather be last in someone’s top 20 producers than be their top female producer.” Lee doesn’t want a pass because she’s a woman, but simultaneously understands that “electronic music is traditionally 1) male and 2) white,” as she explained to Kore Asian Media. “There aren’t a lot of minorities, period, in dance music, and even fewer women . . . As a role model, I want other women to see what I’ve done and know that they can do it, too.”

With influences like Björk and Missy Elliot, we should expect nothing less. Both have been powerhouses in their own right for decades, and artists Lee hopes to work with one day. “They have always been my childhood heroes,” she proclaims. “They set themselves apart by being explicitly unique and different, yet not pretentiously so. The autonomy they have in how they control their craft is also something I respect a lot.” Depressingly, in 2016 it was estimated that only roughly seven percent of the Audio Engineering Society’s members were women, and no woman has ever won a Grammy for producer of the year for a non-classical piece. Even Björk had to set the record straight that she did indeed produce much of her 2001 album, Vespertine, explaining, “It feels like still today, after all these years, people cannot imagine that [a] woman can write, arrange or produce electronic music.”“I don’t think I deserve any passes, either,” she continues. “Don’t book me just because I’m a female producer. But when it comes to integration, let’s fight for it—let’s get women into the Top 10 DJs of the world list.” Lee understands that there’s still room for intersectionality in the electronic world: “It’s something I’m aware of and try not to focus on outwardly, but I’m proud of the music I make. If it touches you, there’s nothing more important.” Lee’s contributions to the electronic music scene have illuminated how powerful women in the industry can be—when they’re given the chance.

Ultimately, we’re currently experiencing yet another shift in consciousness and women are leading the charge, ready for progress. Lune Rouge, like the eclipse or a red moon, is about more than astronomy or music—it’s about culture. It has the potential to elevate us in celebration of duality and enlightenment. Just as many see the 2017 Great American Eclipse as a gift to our divided nation, we should also see the raw release of Lune Rouge as a disruption to the autonomy men have held over the music industry, and recognize the beauty behind the generosity of Lee’s latest release. “I faced some of the most difficult and uplifting moments of my life,” imparts Lee. “Seeing myself at the edge of my own mortality and how I chose to move past [it] is a story told in this album. Each song is its own story and vision, and the album is this overlaying theme of personal freedom and joy.”

“As a woman, I am proud and happy with who I am,” Jennifer shares—as all women should be—and we are proud to highlight her as the cover of our Women’s Issue. With the music and film industries finally openly discussing the value of women in their respective fields, as well as recognizing systemic problems that place less value on women than their male counterparts, we hope this shift in consciousness will lay the foundation for men to stand with women; for women to work together until there is real accountability and an acceptance of an equal artistic evolution.